Looking for Life on Titan.

Titan is a lot like Earth, but can it sustain life?

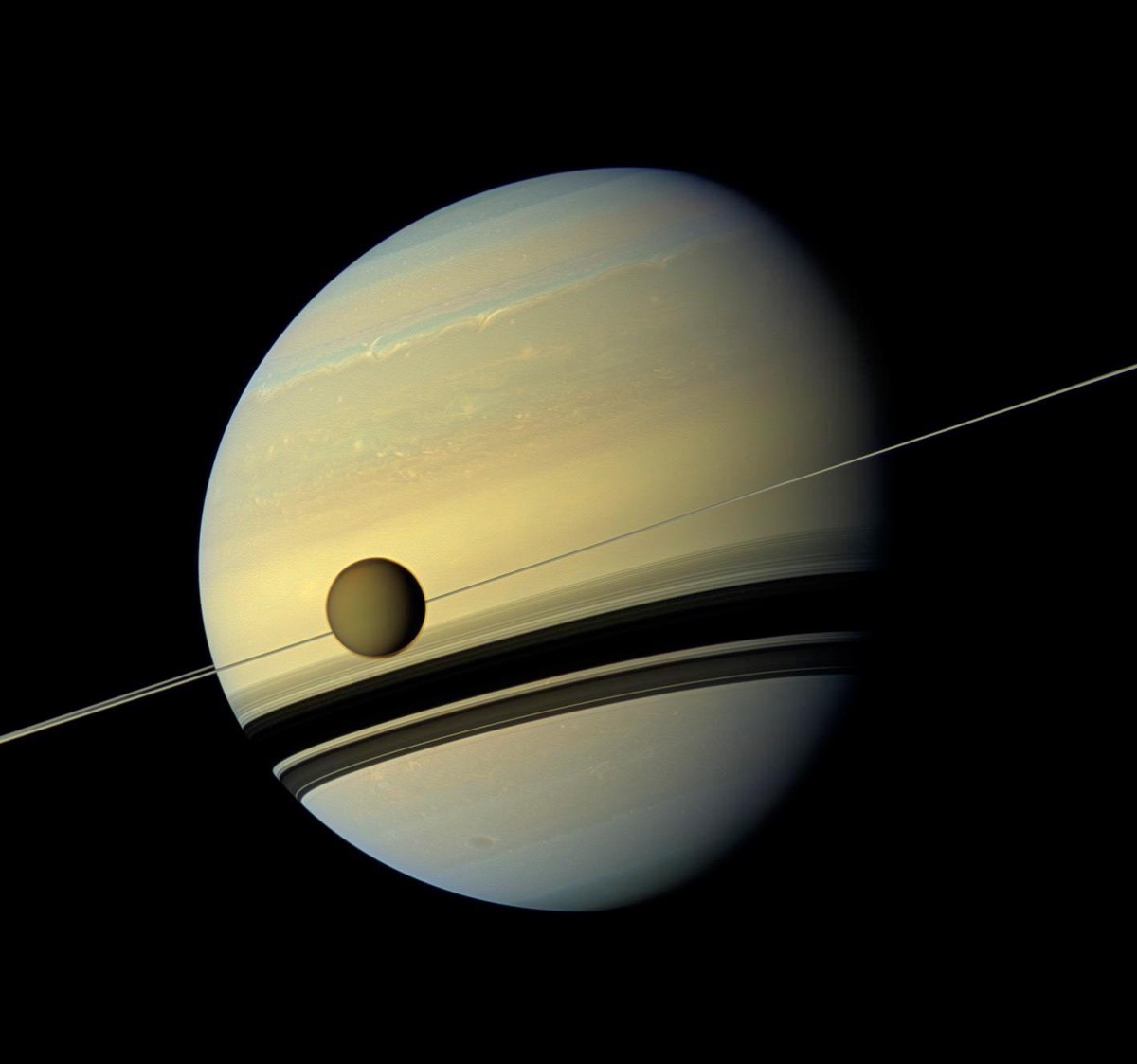

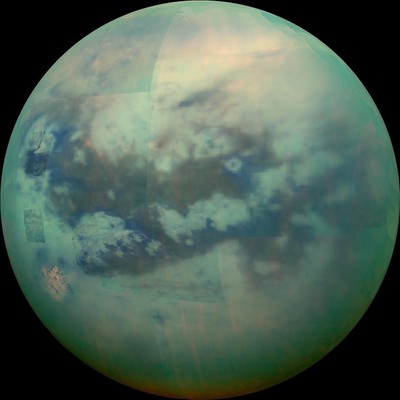

A natural color view of the northern, sunlit side of Titan, constructed from images taken by the Cassini spacecraft.

A natural color view of the northern, sunlit side of Titan, constructed from images taken by the Cassini spacecraft.Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

The solar system is a hostile place. Venus has clouds of sulphuric acid and temperatures high enough to melt lead. The storms on Jupiter are as big as several Earths and of such ferocity that it would put our hurricanes to shame. Dust storms on Mars can cover the whole planet. On Triton, pink snowfall slowly descends upon the surface; it is nitrogen, frozen solid. And yet, astrobiologists dream of life everywhere: in the clouds of Venus, in the dead riverbeds of Mars, in the plumes of Enceladus and in the sub-surface ocean of Europa. One of the most promising places is Titan. It has lakes of liquid methane. It has a dense atmosphere, so dense in fact that human being could fly with strap-on wings! Accompanying all this is a rich atmospheric and surface chemistry. It even rains on Titan. Droplets of methane and ethane slowly float to the surface, forming a soft drizzle. A lot of details about this chemistry were revealed through Cassini and the Huygens probe that it dropped through Titan’s atmosphere, onto it’s surface. The measurements of their instruments revealed a diverse library of molecules.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona/University of Idaho.

But could these molecules lead to life? Titan has thus become a testing ground for astrobiologists: it could provide them with a blueprint for how nature could go towards the formation of more and more complex molecules (like amino acids and DNA, but not neccesarily) that would eventually lead to life, without liquid water or oxygen, at very low temperatures (90 - 94 K), and with timescales as long as the age of the solar system.

The first question that we should ask is this: what could possibly stop Titan from making more complex molecules? The answer is simple: low thermal energy. Sunlight could act as a simple source of energy and power photochemistry in the atmosphere. This produces acetylene, hydrogen cyanide and hydrogen which are all very reactive and could drive reactions on the surface that are exothermic (that is, reactions that release heat). This could support the metabolism of methanogenic forms of life (that is, life that use methane as an energy source). But if we are dreaming of finding bacteria on Titan, we are missing an essential ingredient: cell membranes.

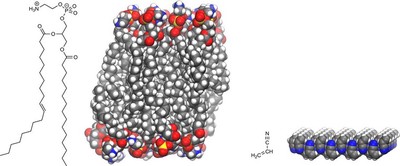

Cell membranes are thought to be essential for life, even for life on other planets, because there are supposed to protect the molecular machinery inside the organism that powers its metabolism. It also selectively screens nutrients from the outside, enable communication between different cells, and allows waste disposal. This is a simple extrapolation from observations of living systems on Earth, that rely on membranes formed of two layers of lipids, a.k.a. fat molecules. These are known as phospholipids (fat molecules with a phosphorus head group). However, these kind of membranes cannot form on Titan, becuase it lacks water and oxygen (which helped form them here on Earth).

In 1957, Oparin suggested for the first time that collodial droplets and could be precursors to cells (this is still being investigated). In 2015, Stevenson et al.1 suggested, in a seminal paper, that azotosomes, small molecules with a nitrogen, instead of a phosphorus, head group, could form be a simple and widely available ingredient for cell membranes on Titan. Simulations predicted that acrylonitrile ($\mathbf{C_2 H_3 CN}$) would form cell membranes of a similar elasticity as the lipid bilayers do here on Earth. These models also predicted that the structure of the membrane would be kinetically persistent; that is, it would not react with anything at a rate fast enough to matter, which implies that, if formed, it would survive at the lowe temperatures of Titan.

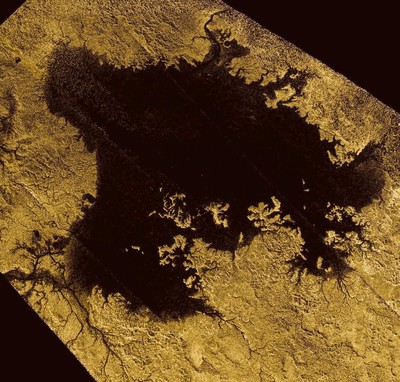

2 years after this prediction, the Atacama Large Millimetre Array (ALMA) discovered large amounts of acrylonitrile on Titan. The data suggested that enough of it was avai;able on Titan to form 10 million cell membranes per cubic centimetre in Titan’s sea, Ligeia Mare. So we know that the building blocks for these cell membranes are available, and, if formed, they will survive. But how will they form? And how do cell membranes form in general?

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI/Cornell.

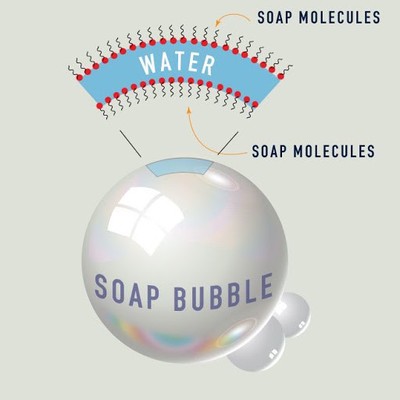

Let’s think of an analogy: soap bubbles! Soaps is formed from molecules that look a lot like the molecules that form cell membranes: a long carbon chain, with a polar group on top. The polar group (usually a sodium or potassium ion) lets the soap dissolve in water, while the long carbon chain lets the soap mingle with dirt and oil. The soap is, thus, a perfect diplomat: it convinces dirt/oil and water to dissolve in each other. It does this by forming structures known as micelles. These form by themselves (in a process known, appropriately, as self-assembly) after the amount of soap exceeds a certain concentration. These are spherical shells of soap molecules, with the long carbon chains on the inside and the polar groups on the outside. These form around dirt particles and oil droplets, trapping them in a cage like structure. The outer layer of polar groups allows them to dissolve in water, and thus soap washes off the dirt and oil from your hands.

Cell membranes can self-assemble as well. The only difference between them and micelles (apart from the choice of building blocks) is that cell membranes are made up of two layers, both of which have their polar groups on the outside, like a sandwhich. This happens because cell membranes here on Earth primarily formed in our oceans, which are composed of water, a polar solvent. However, on Titan, the lakes and seas are composed of liquid methane, which is an organic, non-polar solvent. Thus, our azotosome cell membranes have the opposite polarity, with the non-polar groups on the outside. So, if we want bacteria on Titan, we need these cell membranes to self-assemble. But can they do so?

That is the question that H. Sandström and M. Rahm set out answer2. They decided to simulate these azotosome cell membranes through quantum mechanical calculations. If we wish to have them self-assemble, they should be more stable than if these molecules crystallised into an ice-like solid. They used the popular density functional theory (or, DFT) method to carry out their simulations. This method is preferred for large molecules or group of molecules (such as cell membranes, proteins, and DNA/RNA), because of the lower computational times. While doing their calculations, they also took into account the presence of the methane sea. This sea can stabilise the azotosome membranes through interactions known as dispersion interactions. These interactions occur between non-polar molecules (which lack electric charge) - the molecules induce deformations in the electron clouds of the other molecule, which leads to a dispersal of charge and formation of a fleeting dipole moment. These induced charges can attract one another and enable the formation of complex structures.

They found that the cell membranes were unstable with respect to one of the crystalline phases of acrylonitrile, by about 8000 J per mole. This energy difference may seem small, but it the energy required to place one monomer into the cell membrane. If we calculate how much energy would be required for a 1000 monomers to self-assemble into a cell membrane, the energy difference would be 8 billion Joules per mole! It looks like acrylonitrile would be frozen solid rather than forming cell membranes!

But does life on Titan require cell membranes? Our “lipids-first” or “cells-first” hypotheses of life were drawn from our experiences on Earth. Assuming that these experiences will hold on other planets or moons in our Solar System, or even in exoplanets beyond, may be a horrible fallacy. Looking for life in the Universe may require us to expand our horizons, and to go beyond our experience into the land of imagination. Life on Titan is no different. Are cell membranes even required for life on Titan? They may not be, for, at the low temperatures of Titan:

Life would probably be in a solid state. Thus, there is no risk of it dissolving into the liquid methane ocean, which is what it would have needed a cell membrane for.

Biomolecules would be immobile, which means that the organisms would have to rely on small energetic molecules, like hydrogen, ethane or hydrogen cyanide, to diffuse through to them. Cell membranes coud come in the way of this diffusion and restrict their food source. It would also hinder the disposal of watsre, like methane or nitrogen.

Only reactions with a small barrier height can occur, and these reactions cannot damage any macromolecules that may form. Thus, a cell membrane’s protection may not be required.

Of course, this is all speculation. It is up to future astrobiologists to dream up more outrageous and plausible scenarios for what kind of life could exist on Titan, and for missions, like the Dragonfly spacecraft, to verify whether life actually exists there.

Will we find aliens on Titan? Maybe, but not the kind you think 👽 !

References and Further Reading

Membrane alternatives in worlds without oxygen: Creation of an azotosome, J. Stevenson, P. Clancy, J. Lunine, Sci. Adv. 1, e1400067 (2015). You can find it here. ↩︎

Can polarity-inverted membranes self-assemble on Titan?, H. Sandström and M. Rahm, Sci. Adv. 6, eaax0272 (2020). You can find it here. ↩︎