DIBs: The Greatest Mystery in Astrochemistry

Can we solve it?

Time for some time travel (pun intended)…

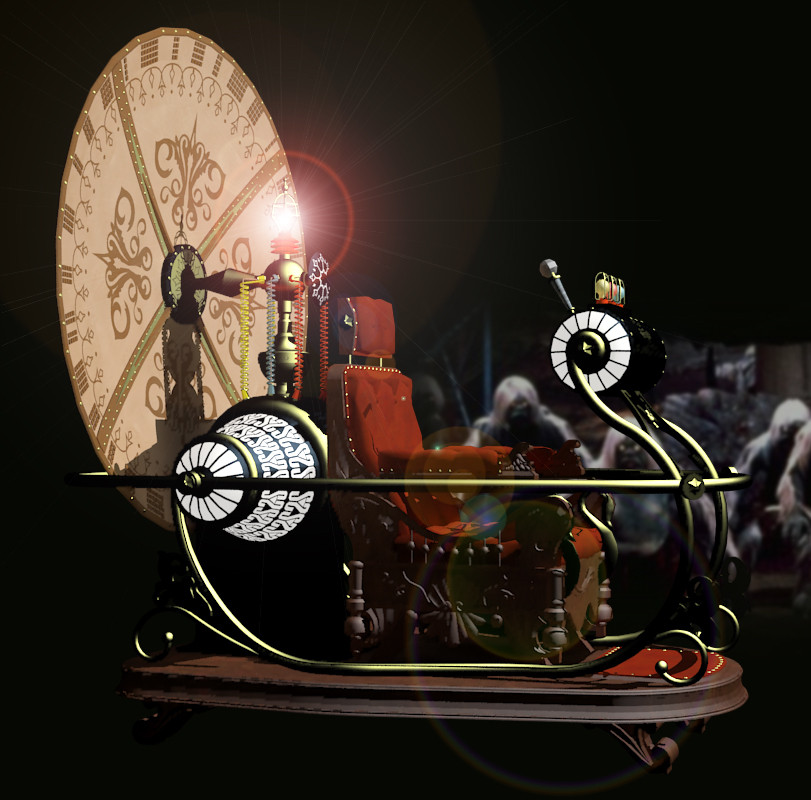

Time for some time travel (pun intended)…Get in, we are going on a trip. Where? More like when! We are going to transverse time and space to try and solve a century-long scientific mystery. First stop, 1919! Hold on tight. The machine lurches. Reality flickers, like a candle in a gust of wind. You don’t know if you are going through time, or if time is going through you. But its over before you know it. You stumble out of the machine, and look around.

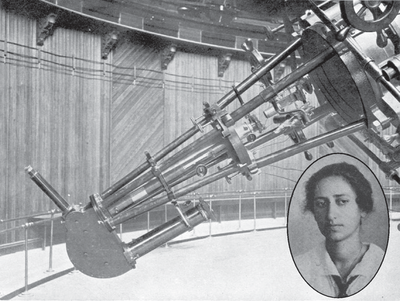

You are on the top of a hill. An observatory dome towers over you. Where are we, you ask? We are at the famous Lick Observatory. In 1919. Right now, Mary Lea Heger is observing two stars from the 36-inch refractor, inside that dome you just saw. She is a PhD student studying the spectra of stars, particularly bonary stars. But today she is looking at two non-binary stars: $\zeta$ Persei and $\rho$ Leonis. Soon, when she analyses the photographic plates she gets, she will detect two lines, at 5780 and 5795 Angstroms, that she won’t be able to identify. She doesn’t know this yet, but these were the first molecules that we ever discovered in space! And they are still unidentified!

In 1919, they were just two of those lines, but now (almost a century later) we know of more than 500 lines like that. These are the Diffuse Interstellar Bands (DIBs). The only thing we can say for sure, based on how strong these lines are, and how squiggly they are, that they must be from molecules that are abundant throughout the interstellar medium. Over the years, scientists have narrowed it down to carbon-containing molecules, like long radical chains, or polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). PAHs are large molecules made of several fused benzene rings. They are believed to be quite abundant in space, but none of their lab spectra has been matched to spectra from space. But there is still hope! And that hope comes in the form of fullerene. Fullerene (also known as buckyball) is an allotrope of carbon (just like diamond, or graphite) that consists of 60 carbon atoms, connected together in a soccer ball like structure. They are named after the architect Buckminster Fuller, an architect who made buildings that looked a like it.

that he designed.](/post/dibs/fuller_building_huc3d9bd29fbeeed7220ae5e545c84f6a5_595603_b2c9c3a14259254b04d50f2c158414ea.jpg)

Okay, lets go back. We have to go to a different space and time now. Any guesses? This time we are going 75 years into the future! That should put us right in 1994. Here we go! I push the lever and the surroundings flicker and vanish. This time you are more used to the weird feeling that accompanies time travel, and when the machine stops you get down without stumbling. Why 1994? Because B. Foing and P. Ehrenfreund are here, and they are about to observe two really strong bands, at 9580 and 9642 Angstroms. See that dome over there? That houses a 1.5 meter Coudé telescope, with a spectrograph (named Aurélie), which they are going to observe the spectra of 7 stars.

They will match the bands to two lines observed in the lab for the fullerene cation, $\ce{C_60^+}$. These lines were recorded using a technique called matrix isolation sepctroscopy. I know, that is a lot of words, so let us break it down! You see, whenever we take a spectra of a molecule, it can be affected by a lot of things: the temperature, the technique used, and the surroundings. If there are other molecules in the surroundings of the molecule we are observing, that can change the spectra. How? Through interactions. If they interact with the target molecule, they can affect the spectra. To avoid all of that, chemists can trap a molecule in a matrix, by freezing it with an inert gas like neon or argon. Since inert gases don’t interact with the molecule much, we get a spectra that is clean and sharp. But there is a little bit of a hitch.

You see, a molecule trapped in frozen neon is not really like a molecule in the gas phase. And the spectra we observe in space is from gaseous molecules. So what do we do? We cheat! We extrapolate the values we get to what they should be if the molecule were a gas, and we compare that with the spectra from space. But, since we are guessing, our values have a certain error attached to them. For all this to work, the error in our guesses should be small. Why? Because there are, frankly, too many DIBs! In the entire range from 4000 to 10000 Angstroms where DIBs are found, there is, on average, at least 1 DIB per Angstrom. So if our error is big enough, we can never be sure which DIB it actually is that we are matching our molecule to.

That’s why astrochemists decided to take on the challenge, and try to take a gas phase spectra of the fullerene cation. “No more cheating!”, they said. But this wasn’t going to be easy. You have to make fullerene first, then vaporise it, ionise it, and take a spectra. If enough quantities of fullerene cation is not produced, the spectra won’t be bright enough to be observed in the first place! So, astrochemists ended up cheating. This time though, they just cheated better.

How did they do it? They took a fullerene cation, attached an He atom to it through a weak bond, and then later broke the bond, using a tuned laser. When the He atom broke away, the mass of the complex decreased. This can be detected. Since the whole process is dependent on the frequency of the laser, we can take the whole spectra by just repeating this process across the whole frequency range. And while it is still surrounded by He atoms (which could affect the spectra), the extrapolation is better this time. Enough to match the lines to specific DIBs!

So did we end up solving the mystery of the DIBs? For that, we gotta go back! Jump in! The time machine vanishes, leaving behind no trace. As you get back to 2020, you wonder what the answer will be. Did we do it? Well, not yet. We have been trying though, getting more and more data from telescopes both on the ground, and out there in space, but the mystery of the DIBs remains unsolved. It is incredible, how we still haven’t indentified the first molecules we ever discovered in space. Who knows when we will find the answer?