Of Demons, Engines and Erasers

When chemists trapped a demon in a bottle…

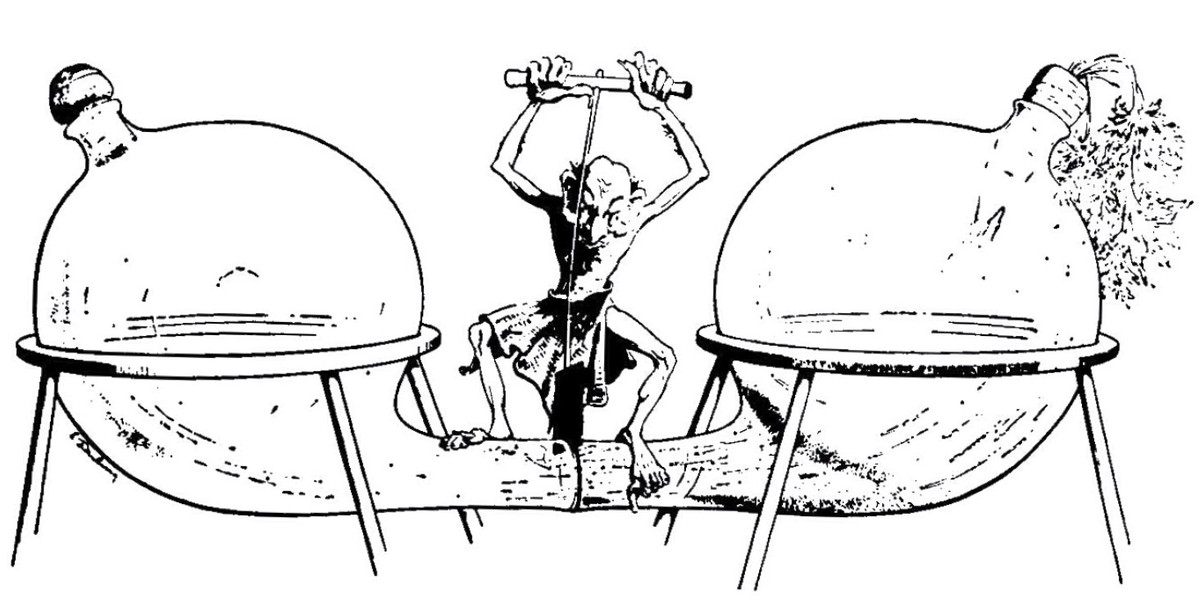

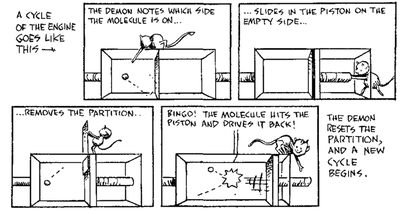

An old illustration of the Maxwell’s demon at work.

An old illustration of the Maxwell’s demon at work.In all of science, nothing is as discouraging and hopeless as the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The law simply states that, for an isolated system (a system that exchanges no mass or energy with it’s surroundings), disorder must increase. Our machines heat up and break down, our coffees grow colder, and, soon enough, everything is averaged out to pure, random molecular motions. It is no wonder that physicists have been trying to evade the Second Law, inventing more and more outrageous scenarios that could violate it. Most of these scenarios involve the notion of a perpetual motion machine of the second kind (“of the second kind” means that it violates the Second Law; “of the first kind” would be a machine that violates the First Law, the conservation of energy!). It can convert the heat in a system directly to work, going on forever, without any need for a power source. Even James Clerk Maxwell was guilty of inventing one 1, a “demon” that exploited the limitations of the Second Law.

To see what hell this demon can unleash, consider a box of gas divided into two compartments. Maxwell imagined a tiny, intelligent being that operates a trapdoor in the partition separating the two compartments and has the power to observe the single atoms of the gas. It would then move the trapdoor (which is assumed to move without any friction) in such a manner that “fast” molecules from the right compartment went left, and “slow” molecules from the left compartment went right. Eventually, the left compartment would have only fast molecules and the right compartment would have only slow ones. Since heat is just molecular motion, the left compartment is now hotter than the colder one. In other words, the demon transferred heat from a colder body (the right compartment) to a hotter body (the left compartment): it has successfully reversed the flow of heat and openly flouted the Second Law! In this demon’s hell, you freeze even as the flames blaze hotter!

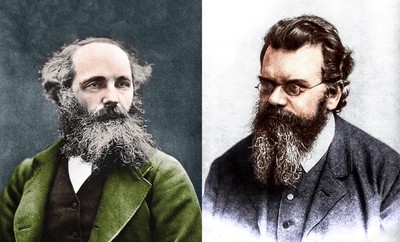

Maxwell, Boltzmann and Entropy

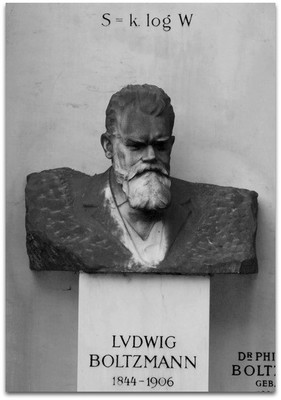

When Maxwell unleashed his demon upon us, he was thinking of the limitations posed by the statistical interpretation of the Second Law, an interpretation we owe to Ludwig Boltzmann. Physicists quantify disorder in a variable known as the entropy of a system: for an isolated system, this entropy is meant to always increase with time. Boltzmann related the entropy to the number of microstates, $W$, of a system: $S = k \, \, ln(W)$, where $ln$ is the natural logarithm and $k$ is the Boltzmann constant, a proportionality factor that, interestingly, Boltzmann himself never used! This famous formula is now inscribed on his tombstone.

What is a microstate? It is the number of all possible combinations of the positions and velocities of all the molecules in the system (such as our box of gas) that leads to a particular temperature and pressure. The more disorder in a system, the more such combinations will correspond to a single point in the $P–T$ plane ($P$ is the pressure and $T$ is the temperature of the system).

With Boltzmann’s approach, the picture physicists had of the Second Law changed considerably: it was no longer a must that the Second law hold, but only more probable that if one started from a state of more order, one would eventually reach states of lesser and lesser order. To ensure that the Second Law applied to our Universe, one would need to have a very ordered initial state (the Big Bang itself). And even then, there was still a non-zero probability that the Second Law could be violated (as first realised by Poincaré), although, as Boltzmann pointed out, the time one would have to wait for such an event would be much longer than the age of the Universe! So if you wait long enough, you can see your coffee boil up on it’s own. You just have to wait for a billion billion ($10^{18}$) years! 2

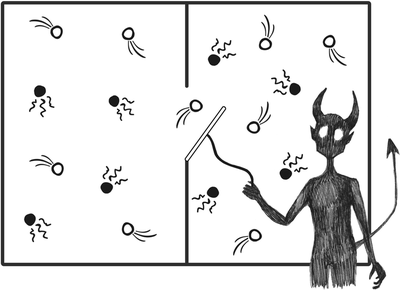

Leo Szilard, in 1929 3, decided to put our clever hellion to work on an imaginary machine which is now known as a Szilard engine. It’s a closed box, with a movable partition in the centre and a frictionless piston at each end. There is only one gas molecule inside. The demon notes which side the molecule is on. If it’s on the left side, it slides in the piston on the right and removes the partition. The molecule collides with the piston and pushes it back. It then resets the partition and repeats the process all over again. Our demon has, once again, violated the Second Law, by converting the random motion of the molecule (that is, heat) into the piston’s orderly slide (that is, work). In other words, a perpetual motion machine.

Or is it?

In order to classify the engine as a perpetual motion machine, the demon must not use any energy from outside. In other words, the Szilard Engine must remain an isolated system. Careful analysis shows that all moving parts of the engine can be made to use vanishingly small amounts of energy, if operated slowly enough. Even observing the position of the molecule requires no energy. But our demon has to have a record of which side the molecule is on: in other words, he has some form of a memory, where he stores the current position of the molecule during each cycle of the engine. In other words, our demon stores some information about the molecule.

But what is information? A rather intuitive answer would be “what we don’t already know”. If someone told you that the Earth revolved around the Sun, you will learn nothing new: the message has no information content at all. But if someone told you the state of the stock market tomorrow, that would be very valuable information indeed, and possibly make you quite rich! To quantify the notion of such information content, Claude Shannon introduced the concept of the information entropy 4, $\mathcal{H}$, inspired by the entropy that was already well known in thermodynamics. Consider storing a bit of information: in other words, storing information in a system that can take on two states – up/down, left/right, magnetised/unmagnetised (like our hard disks). A bit can be either 0 or 1, with equal probability, and the information entropy associated with it is $\mathcal{H} = ln(2)$. Our little rascal also needs only one bit to store the position of the molecule: 0 if it’s on the left, 1 if it’s on the right. The demon would observe the molecule, store a bit of information, use it to move the piston, and then erase that bit and start again.

Enter Landauer: in 1961, Rolf Landauer showed 5 that, while acquiring and storing information may not cost us any energy, erasing information does cost us something, since it is logically irreversible. When erasing information, we go from a particular state of the device to an empty slate; to go back, we need information about what state the device was in, which we no longer have, since we threw it away. In other words, information erasure is not reversible: we cannot “unerase” it. Landauer showed that a physical system that stores a bit must consume atleast $kT ln(2)$ amount of energy. This is now known as Landauer’s erasure principle.

In 1982, Charles Bennett, using the work of Landauer, proceeded to resolve the paradox of Maxwell’s demon 6. Since our engine has two states, when it completes a cycle it reduces its entropy by $S = k ln(2)$ (because it has two states, i.e., $W = 2$; notice that, since $\mathcal{H} = ln(2)$, $S = k \mathcal{H}$. This is not a coincidence; $\mathcal{H}$ and $S$ are the same, except for a factor of $k$). The energy it produces, then, is $k \, T \, \, ln(2)$. Bennett demonstrated that the amount of energy our little demon produces is always equal to, or lesser than, the amount of energy it has to consume to erase his one bit. Thus, it can never actually produce any energy; it has to use all of it to erase the bit he has stored, and start over, like Sisyphus. The Second Law lives on!

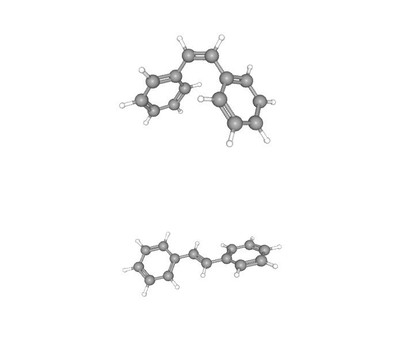

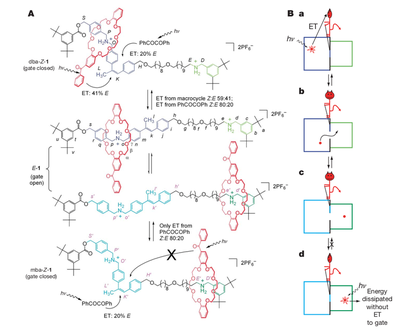

For years, Maxwell’s demon has remained in the realm of wild imagination and theory. Rapid technological progress has enabled us, however, to manipulate individual atoms and molecules, and rigorously study Maxwell’s demon in the laboratory. David Leigh and colleagues at the University of Edinburgh 7 realised a chemical version of Maxwell’s demon using a rotaxane molecule. A rotaxane molecule consists of a molecular “wheel” threaded onto an “axle”. The “axle” has a kink in it in the form of stilbene (two benzene rings linked together by a double bond; see it’s structure below). Stilbene has two isomers: E and Z. In the E-isomer, the benzene rings are on opposite sides; in the Z-isomer, they are on the same side. Converting the E-isomer to the Z-isomer undoes the kink and allows the “wheel” to pass through to the other side; that is, stilbene is our “gate”. At both ends of the “axle”, we have two groups that can bind the crown ether (which is the “wheel"): dibenzylammonium (dba) and monobenzylammonium (mba). Both groups bind to the “wheel” with similar strengths and act as our left and right compartments; since dba binds to the “wheel” a little more strongly, it is our left compartment, and mba is the right one.

To open and close the gate, we use two compounds: benzophenone and benzil. When the solution is irradiated with light at 350 nm wavelength, benzil stabilises stilbene so that an Z:E ratio of 82:18 is reached; while benzophenone does the opposite, stabilising stilbene such that the Z:E ratio skews to 55:45. Benzophenone has the added advantage that it could successfully be incorporated in the structure of the “wheel” itself. Thus, when the solution (which has 100% E-isomer, i.e., all gates are closed) is irradiated for $\sim$ 25 minutes, the dba:mba ratio goes from 100:0 to 65:35, as benzophenone opens the gates in some of the rotaxane molecules. After the addition of an equivalent of benzil, the dba:mba ratio has dropped further to 58:42. After adding about 5 equivalents of benzil, all gates close (the Z:E ratio goes from 66:34 to 80:20) but the dba:mba ratio has been flipped to 45:55. Thus, about a third of all the “wheels” in the solution have, through random motions, shifted from the left to the right compartment (see the figure below); it can be shown that this move lowers the entropy of the system.

Just as in Maxwell’s thought experiment, the subtle cost of energy has to be paid through the transfer of information. While, in practice, the conversion of photonic energy to heat occurs in many places during the operation of our nanomachine, most of these heat losses could be theoretically eliminated by changing some detail or the other in the design of the experiment. The only part of the mechanism where there is an unavoidable heat loss is during the opening and closing of the “gate” by benzophenone. When our “gate” is excited, the transition to the higher energy state occurs without any change in the structure of the molecule. This fact, known as the Franck-Condon principle, is a consequence of the motion of the electrons in the molecule being faster than the motion of the heavier nuclei. After such a “vertical” transition, the molecule relaxes to a “perpendicular” state, which is intermediate between the E- and Z-isomers; it then further rearranges itself into the final Z or E product. Both these processes (the relaxation to the perpendicular state and the subsequent rearrangement) require dissipation of energy as heat. This process erases the information about the wheel’s probable location from the memory of our “demon”, in agreement with the resolution of the paradox of Maxwell’s demon that we just discussed. There are many other ways Maxwell’s demon and the Szilard Engine have been realised in the lab; see 8.

Maxwell’s little thought experiment has had numerous consequences for thermodynamics, statistical mechanics and information theory. As our processors grow smaller and smaller in size, we are slowly reaching the thermodynamic limit placed by Landauer: soon, computer scientitsts and electronic engineers may have to face the demon again, and win. The demon has even showed up in the study of quantum computers, nanomachines (molecules that can carry out mechanical operations, such as those of a motor; rotaxane is one such molecule), biology (our cells can be considered as machines with the DNA acting as memory!) and even cosmology (the cosmological arrow of time and the “heat death” of the Universe; see 9). In spite of being alive for more than 150 years, Maxwell’s demon is still alive and well, and continues to inspire scientists across all disciplines.

References and Further Reading:

Theory of Heat, Maxwell, J. C. (1867, Fourth Edition): This is the first time that Maxwell presented his demon in a public presentation. Earlier mentions can be found in his letters to P. Tait. ↩︎

For a scientific biography of Boltzmann with excellent discussions of the history and physics of statistical mechanics, do check out: Ludwig Boltzmann – The Man Who Trusted Atoms, Cercignani, C., Oxford University Press (1998, First Edition). ↩︎

On The Decrease Of Entropy In A Thermodynamic System By Intervention Of Intelligent Beings (translated from the original German version: Uber die Enfropieverminderung in einem thermodynamischen System bei Eingriffen intelligenter Wesen which appeared in the Zeitschrift fur Physik, 53, 840-856 (1929), by Anatol Rapoport and Mechthilde Knoller), Szilard, L.: This is where Leo Szilard first presented his hypothetical engine, and established one fo the earliest connnections between information and entropy. ↩︎

The Mathematical Theory of Communication, U. Illinois Press (1963), Shannon, C. E., Weaver, W.: One of the first presentations on the information theory, where Shannon introduced the concept of the information entropy \mathbf{H}. ↩︎

Irreversibility and Heat Generation in the Computing Process, Landauer, R., IBM Journal of Research and Development, 3, 183-191 (1961): Landauer’s presentation of his erasure principle, where he establishes that the erasure of information is logically irreversible and then shows that every such process releases energy of the order of \mathbf{kT} in the form of heat. ↩︎

The Thermodynamics of Communication – a review, Bennett, C. H., Int. J. Theor. Phys. 21, 905 (1982): The resolution of the Maxwell’s demon paradox by Charles H. Bennett. ↩︎

A Molecular Information Racket, Serreli, V., et al., Nature 445, 523 (2007): The implementation of Maxwell’s demon using a rotaxane, a molecular nanomachine. ↩︎

Other implementations of Maxwell’s demon also exist. See: Comprehensive Control Of Atomic Motion, Raizen, M. G., Science 324, 1403 (2009); Experimental Demonstration Of Information-To-Energy Conversion And Validation Of The Generalized Jarzynski Equality, Toyabe S., et al., Nat. Phys. 6, 988 (2010). ↩︎

For some excellent discussions of entropy and it’s relation to the cosmological arrow of time, you could go through two excellent works by the famous cosmologist, Roger Penrose (a close collaborator of Stephen Hawking): Emperor’s New Mind, Penrose, R., Penguin Books (1991); Cycles of Time, Penrose, R., The Bodley Head (2010). ↩︎