The Dark Stars

When the Universe was young, the dark stars ruled the lands…

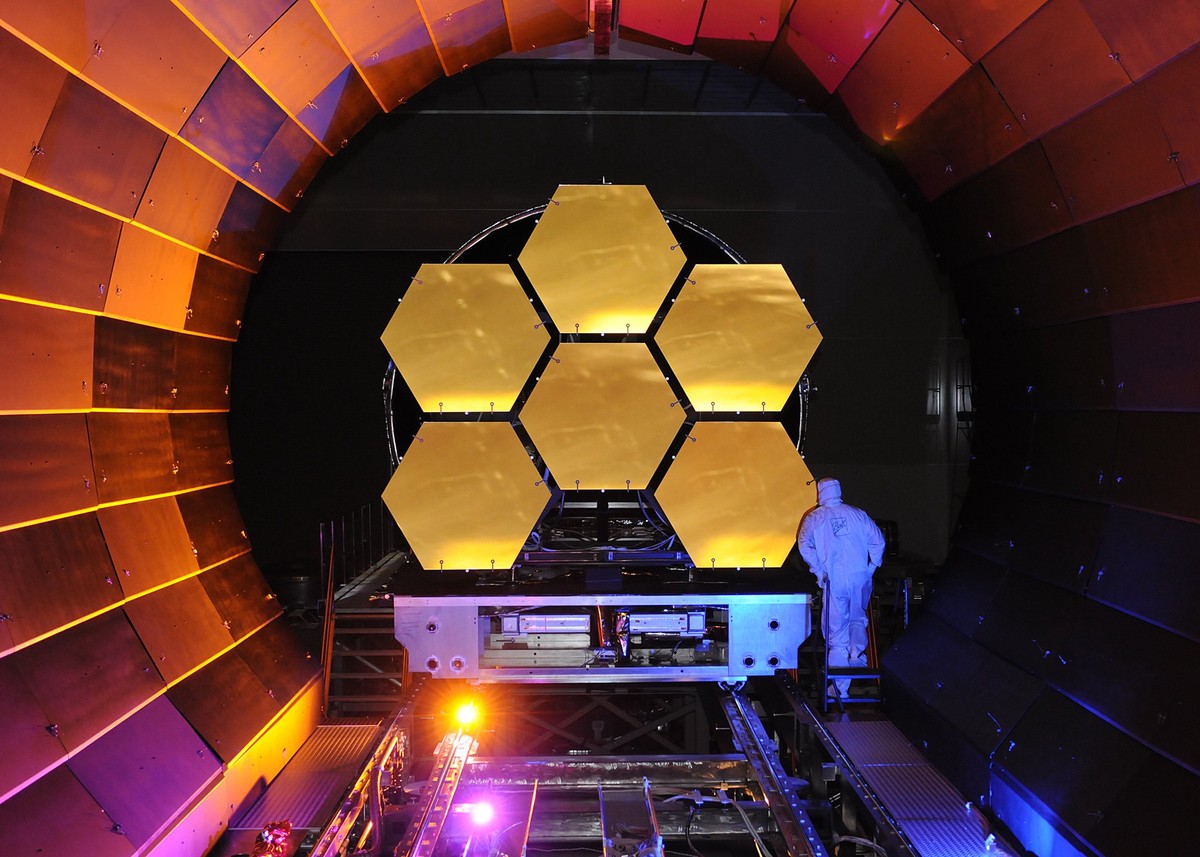

An engineer examines six of the 18 JWST mirror segments after a test.

An engineer examines six of the 18 JWST mirror segments after a test.The JWST may help us discover dark stars.

Credits: Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp.

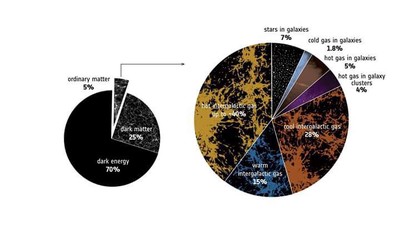

Once upon a time, our Universe was simple. It was made of stars, galaxies and clusters of those galaxies. But then, it began to get complicated. Really complicated. First astronomers discovered a type of matter that they could not see: dark matter. While it never interacted with light or emitted any light on its own, it gravitationally attracted the ordinary matter around it. And this is what made it so important: to keep the stars in the galaxies and galaxies in the clusters, there needed to be more matter than could be seen through our telescopes. Dark matter became the cosmic glue that was necessary to keep the Universe from breaking apart. And then the story became even more muddled, when scientists discovered that something was powering the expansion of the Universe: it was accelerating, with galaxies moving apart from one another with greater and greater speeds. This mysterious force became dark energy, and is alone responsible for most of the energy content of the Universe today. Only one fourth of the Universe is made of dark matter, leaving only a measely 5% for all matter that we can see (known as baryonic matter because it is made up of baryons; protons and neutrons, which form all known matter, are baryons). The rest (about 70%) of the Universe is made of dark energy. But this is not dark energy’s story. This is the story of dark matter; of the time when the Universe was merely 200 million years old and the first stars were being born. There was a lot of dark matter around in those days. And it gave rise to stars of its own: the dark stars. These stars are not like normal stars. They are giant, puffy star-like objects which are powered, not by nuclear fusion, but by the annihilation of dark matter with itself.

It is believed (according to one of the many theories about dark matter; this is just one of the more widely accepted ones) that dark matter consists of WIMPs - Weakly Interacting Massive Particles. These particles arose naturally in many alternatives to the standard model of particle physics before anyone even knew that dark matter existed, such as supersymmetry (a.k.a. SUSY). SUSY claims that every particle has a “superpartner": the electron has the selectron, the proton has the sproton, and so on. The lightest of all these particles is a WIMP. It can be its own antiparticle, enabling WIMPs to annihilate one another. If we assume that WIMPs were in thermal equilibrium with the Universe when it was born, we can predict how many of them will be left behind today as they annihilate themselves into photons. Such a calculation predicts a dark matter density very close to the actual value today. This surprising coincidence is known, appropriately, as the “WIMP miracle”, and is the reason why they are considered as one of the best candidiates for dark matter today. Even a small concentration ($\sim 0.1 %$) of such particles could power a star for million and billion of years. Dark stars are huge ($\sim 10$ AU; 1 AU is the distance between the Sun and the Earth and is equal to kilometres!) and cool (surface temperatures of $\sim 10,000$ K; for stars, that is really cool).

.](/post/dark_stars/darkstarsonHRdiagram_hubaaae4ad5ac619a4a27a1cebb528b5dd_273937_e19e7dbe4c2bb9a15496f2bded948452.jpg)

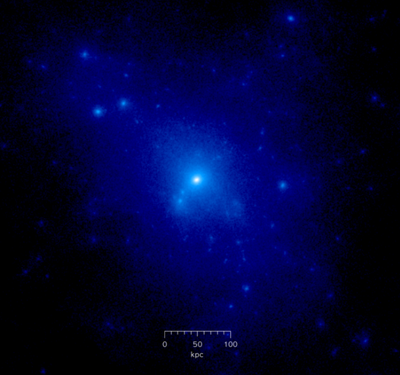

The dark matter is only a small part of these stars; most of their mass is comprised of hydrogen and helium, just like the first stars. They were born during clumpy times in the Universe. Dark matter and normal matter were together forming lots and lots of clumps, smaller than the Earth. These clumps came together to form bigger and bigger clumps, until eventually we had the stars, galaxies and galactic clusters that we see today. This is known as hierarchial clustering. These big clumps, known as dark matter halos, were rugby-like objects, with $\sim 85 %$ dark matter and $\sim 15 %$ normal matter in them. These halos were the sites of formation of the first stars, also called Population III stars.

At the center of these halos, where dark matter densities were the highest, dark stars formed. While they must have been only as heavy as our own Sun when they were born, they accreted mass from the surrounding gas clouds and grew to be huge, with almost tens of millions times the mass of our Sun. They were billions of times luminious than our Sun too. While Population II stars were massive too, they were never as massive as them: there masses were only $\sim 140 M_{\odot}$. This was because they were hotter (surface temperatures of $\sim 50,000$ K) and they ionising photons produced through nuclear fusion prevented further accretion of matter. When the fuels runs out, these “massive” stars collapse directly to black holes.

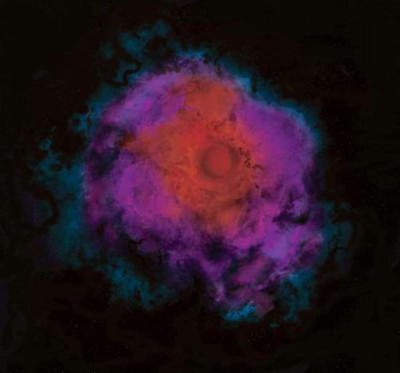

But what happens when the fuel runs out in “dark” stars? They too collapse under the crushing force of gravity. As they collapse, they either enter a brief period of fusion (transforming themselves into “massive” stars), or directly collapse to black holes (with masses of $10^{4} M_{\odot}$ or greater). These black holes may have been the seeds of the supermassive black holes (or, SMBHs) that are now known to exist at the center of almost every galaxy. These SMBHs have masses millions, or even billions, of times the mass of our Sun. Many such black holes, like the one in the center of our own galaxy, the Milky Way, are dormant. But many others are active, accreting huge amounts of gas and spewing two jets from mutually opposite directions. The gas in these jets is accelerated to speeds close to the speed of light. Since the jet is surrounded by a magnetic field, these gas particles are stripped of their electrons, forming a plasma that starts to radiate all kinds of high-energy radiation, from X-rays to gamma rays. These violent objects are called active galactic nuclei, or AGNs. When many dark stars at the center of dark matter halos collapsed into black holes, these black holes must have merged together to form larger and larger ones, until they became supermassive.

Dark stars, being so luminous, could be detected by the next generation of optical telescopes, most notably the James Webb Space Telescope that is being prepared for a launch date in 2021 by NASA. A successor to the already largely successful Hubble Space Telescope, the JWST will achieve higher resolutions and sensitivities, and observe the Universe at longer wavelengths, from long-wavelength visible through the mid-infrared range ($0.6 - 27 \mu$m). This will enable it to observe the Universe at higher redshifts (that is, objects that are more distant and older) than the HST. It will also use a sunshield to keep all of its instruments at very low ($\sim 50$ K) temperatures, to avoid interference in the infrared. These qualities make the JWST an ideal instrument to probe the birth of the first stars, and detect the hypothesised dark stars as well. But, considering how large and bright they are, how will one differentiate them from, say, dwarf galaxies at similar redshifts? As it turns out, dark stars pulsate. Traditionally, the pulsation of (normal) stars are classified into two modes, depending on which force acts as the restoring factor:

Acoustic or p-modes. Here, radiation pressure is the restoring force.

Gravity or g-modes. As the name suggests, gravity (or buoyancy) is the restoring force here.

Dark stars are not very likely to have any g-modes. Even though they are very puffy, full of gas and radiation, the flow of heat among the layers of gas is remarkably stable. However, p-modes are still possible. These pulsations could be as short as a day, or as long as 2 years. They could be caused by pressure fluctuations, partially ionised layers of hydrogen and helium, or even small changes in the density of both dark and baryonic matter, which could change the rate at which those parts of the star are being heated. If these pulsations were to be detected, they could enable us to use the dark stars as standard candles.

We know that the more distant a star is, the less bright it appears in the sky, even though in reality it may be many times brighter than our own Sun. This fact can be exploited; if we know how much radiation a star radiates, that is, how bright would it be if we could observe it at a fixed distance from us, we could use the relationship between how bright the star actually is and how bright it appears in the sky, to calculate the distance of the star from the Earth. For years, astronomers have used stars called Cepheid variables to do so. These stars pulsate in brightness: the period of their pulsations and their luminosity (how bright they actually are) are strongly related. Measure one and you have the other. They can, therefore, be treated as standard candles and used as markers to calculate cosmological distances. Similarly, at least in principle, dark stars could become standard candles, enabling us to calculate the distance to galaxies at high redshifts with high accuracy.

.](/post/dark_stars/Cepheid_hu59697bef21a5d42d23dd3cb4b80083e3_114836_306d4442c0611f3f71ee0adcd6e24e68.jpg)

The pulsation period is also dependent on the masses of the WIMPs; the more the mass, the shorter the period. Thus, if we observe the periods, we could constrain the masses of WIMPs, helping physicists arrive at the correct model of dark matter. As we build bigger and better instruments to probe the Universe, we should be prepared for bigger and better surprises too, as we discover things beyond our feeble imaginations. Dark stars may be once such discovery.