Crystallising Time

When scientists went ahead and crystallised time!

Symmetry is boring. It implies a similarity, a blandness in things; the more same a thing is, the more symmetrical it will be. Take a white, featureless wall, for example. It is nothing to look at, but it is very symmetrical: reflect it, move it, rotate it, and it remains the same. But what if you notice a black spider, crawling its way up the wall? The symmetry of the wall has been broken. That’s why the spider caught your attention in the first place; our brains are trained to detect patterns and features. In other words, they are always looking out for broken symmetries. That’s why a crystal is such a beautiful thing. It breaks the symmetry of space itself; to ensure that we get the same thing after translating the lattice along any given direction, we have to move it a distance equal to the distance between the ions (or molecules, or atoms; see the figure below). Otherwise it doesn’t work. In slightly more mathematical terms, one would say that a crystal has broken the translational symmetry of space. It now has a discrete translational symmetry in space; move it finite steps and it is still symmetrical.

But remember what Einstein told us? He said that, because of relativity, space and time are all mixed up; now it is spacetime, a 4-dimensional monstrosity. That starts to make you think: what if we broke the symmetry along the axis of time? What would happen then? Would we get a crystal in time? Frank Wilczek1 seemed to think so and he called them (surprise, surprise!) time crystals. He imagined a lump of particles on a superconducting ring, threaded by a magnetic field. In the ground state, his solutions showed that the system oscillated. That is, without taking in any energy, it started oscillating on its own. For those who smell something fishy already, you are not alone; Patrick Bruno smelt it too. He, in one small note2, calculated a lower ground state for the same system that did not oscillate at all. He then ruled out all such periodic rotating time crystals with a “no-go” theorem3. The train of time crystals had been stopped at the station before it could leave.

But the train got another jump start when physicists began thinking about periodically driven systems. The previous version of time crystals had been trying to break continuous time translational symmetry. While quantum mechanics won’t allow that symmetry to break, it allowed one to break the symmetry if it were already a little broken; that is, if the time translational symmetry were discrete.

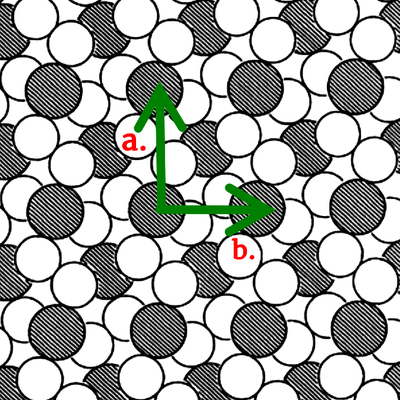

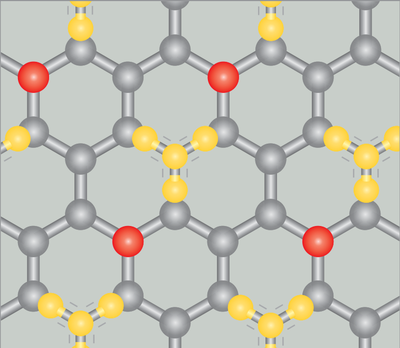

Lets take an analogy in space to get a better feel of what’s happening here. Graphite is one of the crystalline forms of carbon (the other is diamond). The carbon atoms arrange themselves in stacks of honeycomb-like sheets. Like any other crystal, these sheets break the continuous symmetry of space into a discrete symmetry. When we cool down a graphite surface to very low temperatures and let methane gas loose over it, some of the methane molecules get adsorbed. Note the “d” – “adsorbed”, not “absorbed”. In the words of a chemist, this means that the methane molecules remain attached to the surface and don’t wiggle their way between the graphite sheets. Now lets take a camera and snap some pictures of the methane molecules on graphite. At temperatures greater than $\sim$ 60 K, the methane molecules are dancing on the surface, like they would do if they had been liquefied; they have formed a 2-D liquid on the surface. But if we lower the temperature further, the methane molecules stand “still”, occupying fixed positions on the graphite lattice. They have solidified and formed a “sub-lattice“. This sub-lattice is less symmetrical than the lattice of graphite. That means a symmetry has been broken: the discrete space translational symmetry of the graphite crystal.

A time crystal is just like that, but in time instead of space. A periodically driven system is like a swing in the park that has to be pushed continuously. It is discrete in time; when we break that discrete time symmetry, we make a time crystal. But remember: a crystal does not require any energy to remain in equilibrium. In fact, when it forms, it releases energy because it is more stable than the atoms, ions or molecules it’s made up of. Our time crystal must also be in some kind of equilibrium. Unfortunately, a periodically driven system can never be in equilibrium; the swing will go to-and-fro only as long as we push it. But if we take our camera and snap pictures every time the swing goes forward after a push, all our pictures will be the same. Thus, our system could act like a system at equilibrium, if only we observed it at those particular times. This kind of equilibrium is called crypto-equilibrium. However, we have bigger problems. As our system oscillates, it absorbs energy with each push; if we wait long enough, it will heat up more and more until it reaches infinite temperatures! Theoretically, that is. So how do we prevent our time crystals from blowing up?

In classical mechanics, energy is continuous: a classical system will absorb and emit any amount of energy. But we know that this world runs on quantum mechanics and in quantum mechanics energy is discrete. Our quantum system will only absorb and emit certain quanta of energy. So, a periodically driven system absorbs only certain amounts of energy every time. If the rate at which this energy is being given is large enough compared to the energy quanta, the energy absorbed will spread over the many energy levels of the system and this will make the heating up of the system a very slow process. This stage is known as a pre-thermal state. And even this spread of energy can be stopped in its tracks if the components of the systems start to interact in a phenomenon known as many body localisation (or, MBL). Through its interactions, it can trap the excitations in energy and prevent them from going anywhere. Our time crystals, if carefully made, won’t blow up at all: they could exist forever without heating up. But classical time crystals will blow up, unless they are coupled to a dissipative bath. The bath will absorb all the heat and release it carefully, stabilising the crystal, just like a bucket of cool water.

Well, we have made our time crystals. But what do they look like? Recall our methane molecules on graphite. When the methane solidifies, it occupies a sub-lattice over the lattice of graphite. They could occupy either one of two sub-lattices (indicated by the already occupied positions and the positions indicated in red in the image we saw above). Each sub-lattice has half of the positions that the methane molecules can occupy on the main lattice. Similarly, a time crystal crystallises into a sub-lattice in time. This “sub-lattice” is nothing but another periodicity, but one that is different from the period of the drive that’s pushing the system. Intuitively, we could guess that this period would be twice that of the drive (that is, a frequency that is half the frequency of the drive), because the methane molecules occupied only half of the positions in the sub-lattice. This property of time crystals is known as a sub-harmonic response; the system would eventually settle into a frequency of oscillation that will be a multiple of half the drive frequency.

Faraday’s Patterns and Time Crystals

The sub-harmonic response that we just met was, when first discovered in time crystals, was touted as a fundamentally new property that differentiated them from classical systems. In fact:

Any such time crystal should return back to its initial state at specific times, while spontaneously locking to an oscillation period that differs from that of any external time-dependent forces. Hence this definition excludes all known classical oscillatory systems such as waves or driven pendulums. From “How to Create a Time Crystal”, Richerme, P., Physics 10, 5 (2017), page 1.

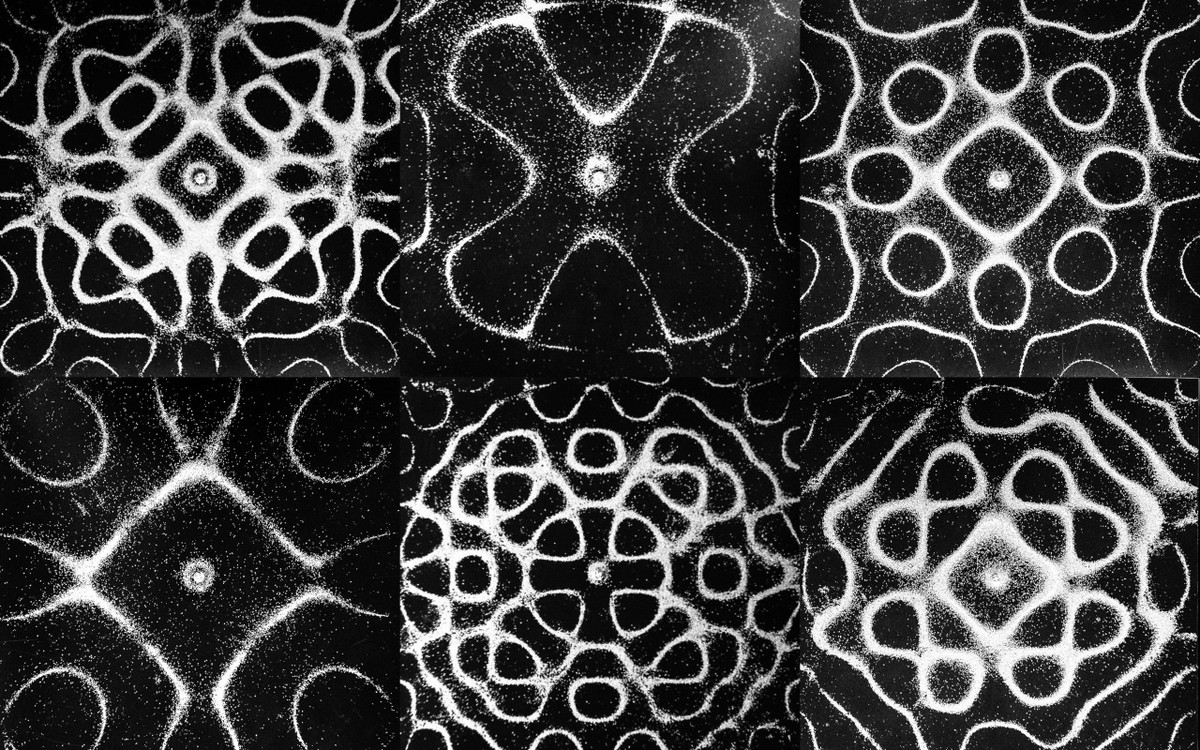

But perhaps Michael Faraday would disagree. In 1831 (188 years ago!) 4, he was studying patterns (known as Chladni patterns) created when powdery materials (like sand) or fluids on a surface (like water) were set into motion by an external drive (like a violin bow; we would probably use a loudspeaker). The amplitude and frequency of these patterns can be changed by changing the force and frequency of the drive.

Video: Chladni patterns formed when sand is excited on a square plate using a loudspeaker.

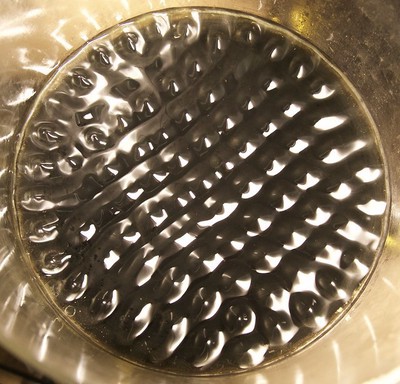

If we excite the fluid weakly, the surface remains flat. As we excite it more and more strongly, the flat surface of the fluid breaks up into beautiful patterns as it becomes more and more unstable. He recorded many beautiful patterns in the appendix of his paper. He eventually slowed down the patterns enough that he could see that the hills and valleys of vibration of the fluid on the surface formed a chessboard-like pattern.

To quote the great man himself:

It could now be observed that the ridges on either side the vibrating plane consisted of two alternating sets; the one set rising as the other fell. For each fro and to motion of the plane, or one complete vibration, one of the sets appeared, so that in two complete vibrations the cycle of changes was complete. From 4, page 335.

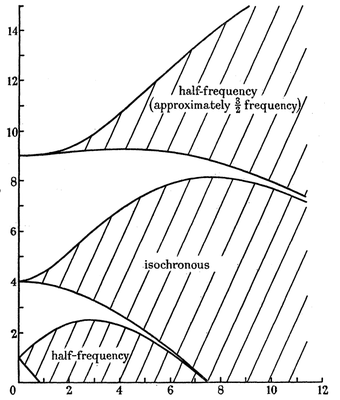

Sound familiar? Faraday saw a periodically-driven classical system (his fluid on a surface excited by a violin bow) break its discrete symmetry in time further and oscillate at a period that was twice the period of the drive. It took 123 years before, in 1954, a theory of this phenomenon, known as the Faraday instability, emerged out of the work of mathematicians T. B. Benjamin and F. Ursell5. They found that the systems Faraday was studying obeyed the Mathieu equation. It’s solutions have well-known properties, the important one being that for a particular set of solutions, the system locks itself into a sub-harmonic response.

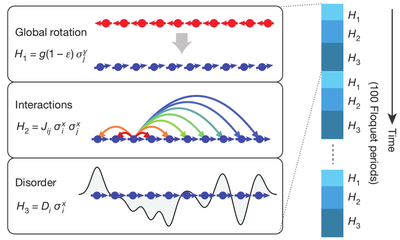

Time crystals may have once sounded like a lubricious theorist’s dream, but, given a firm physical basis through the magic of quantum mechanics, they were rapidly realised in the laboratory. To make them6, a group of 10 ions were stored in configuration of electric fields known as the Paul trap. These ions were trapped in a straight line, since the trap itself is linear. This system oscillated between two states initially: one where all ions had spins aligned on one particular side and the spins flipped to an almost opposite direction, and the other where these flipped spins interacted through many long-range interactions. Then, a laser introduced some disorder. Now, the system flipped between three states: first the spins were aligned in the same direction and then flipped almost completely, then the spins interacted strongly, and then the spins became strongly randomised. The system goes through 100 of such cycles. Eventually, the system settled down to the predicted sub-harmonic response (see the figure below; the cryptic $\mathcal{H}$ is the Hamiltonian of the system, a quantity that characterises the state of the system uniquely. Don’t worry too much about it if you haven’t seen or heard of it before. It just means that the system is in another, different state).

And thus, a time crystal was born.

The experiment could not have been carried out without many of the instrumental methods that scientists now have to trap, control and probe individual atoms, ions and molecules (for more such feats, check out my article on how scientists implemented a Maxwell’s demon in the lab here). Using these techniques, they have even crystallised time.

Wonder what they will do next.

References and Further Reading:

Quantum Time Crystals, Wilczek, F., Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 160401 (2012): The first (but flawed) paper that suggested the idea of time crystals. ↩︎

Comment on ‘‘Quantum Time Crystals’’, Bruno, P., Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 118901 (2013) ↩︎

Impossibility of Spontaneously Rotating Time Crystals: A No-Go Theorem, Bruno, P., Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 070402 (2013) ↩︎

On a Peculiar Class of Acoustical Figures; and on Certain Forms Assumed by Groups of Particles upon Vibrating Elastic Surfaces, Faraday, M., Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London 121, 299 (1831). ↩︎

The Stability of the Plane Free Surface of a Liquid in Vertical Periodic Motion, Benjamin, T. B., Ursell, F., Proc. R. Soc. A 225, 505 (1954). ↩︎

Observation of a Discrete Time Crystal, Zhang, J., et al., Nature 543, 217 (2017) ↩︎