Molecules Blazing from the Distant Past.

An astrochemical peek into our Universe’s past.

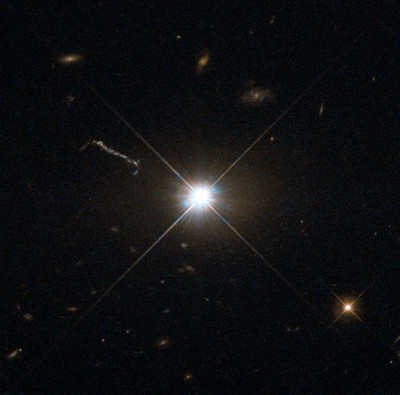

This image from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope shows the distant active galaxy PKS 1830-211. It shows up as a unremarkable looking star-like object, hard to spot among the many such closer real stars in the picture. Recent ALMA observations show both components of this distant gravitational lens and are marked in red on this composite picture. Credit: ALMA(ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/NASA/ESA/I. Marti-Vidal.

This image from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope shows the distant active galaxy PKS 1830-211. It shows up as a unremarkable looking star-like object, hard to spot among the many such closer real stars in the picture. Recent ALMA observations show both components of this distant gravitational lens and are marked in red on this composite picture. Credit: ALMA(ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/NASA/ESA/I. Marti-Vidal.“What if you could race a beam of light?”

You are at the starting line. In position. Ready to move. The gun goes “BAM!”, and, before you can even blink, the laser beam is already ahead of you. You start to run. Drops of sweat go down your brow. Your muscles are screaming. Your ears are ringing as the air howls past you. Releasing all the energy you have left in one final burst of speed, you finally catch up! You turn your head to look at the beam. What do you see?

This might sound like a weird dream, but this is what Einstein was dreaming about when he was 16. Physics at the time told him 2 different, contradictory things: that the speed of the laser beam had to remain the same, even if you ran alongside it, and that if you ran alongside anything, even a beam of light, at it’s speed, you should see it as if it were still. So which is true? Will you see a still laser beam, or won’t you?

![One day, while riding his bicycle, he gazes at the rays of sunlight beaming from the Sun to the Earth and wonders what it would be like to ride on them, transporting himself into that fantasy: 'It was the biggest, most exciting thought Albert had ever had. And it filled his mind with questions.' From [^3].](blazar%5c_chem/onabeamoflight.jpeg)

Einstein finally answered this question with a definitive “NO” when he grew up. In fact, he was sure no one could actually run as fast as a laser beam, let alone outrun it. And so we got our cosmic speed limit: whether it was the light in our lasers, or the light from the stars, all of it had to go at the same speed. This simple fact has all kind of consequences. Think of the light from stars. The nearest star, Proxima Centauri, is almost 38 trillion kilometres away. But the speed of light is only about 300 thousand kilometres per second! That means it will take the light from it almsot 4 whole years before it can get to Earth! Even the light from our own Sun takes 8 minutes to get to us. If the Sun exploded right now, we can go on with our lives for a full 8 minutes before we realise that we are goners.

So most of the light we see when we look at the night sky is old. And when I say old, I mean anything from 4 years to several billion years! Astronomers collect all this light and tell us all kinds of stuff: How do planets, stars and galaxies form? How did the Universe become like this? The older the light, the further back they can look into time.

Is it a star? Is it a galaxy? No, it’s a quasar!

Once upon a time, astronomers saw some really old light. They didn’t know how old it was yet; many thought it was coming from stars in our own galaxy. But if they were stars, they were weird: they emitted a lot of radiation across the entire electromagnetic spectrum, their spectral lines were all over the place, and their brightness changed over hours or days. And then scientists discovered that they could observe radio waves from space. Astronomers, new to the world of radio engineering, started the construction of the first radio telescopes and began surveying the radio sky. The weird stars started turning up again, this time as mysterious radio sources. They could not be matched to anything in the optical sky. It was not until 1962, when Cyril Hazard and John Bolton observed one of them, 3C 273, just as it disappeared behind the Moon (a phenomenon known as occultation). This allowed them to precisely figure out where it was in the sky, and match it to a single star-like object in the Virgo constellation. But it hadn’t been easy: the Parkes Radio Telescope, which was used for the observation, could not tip down enough for the observation, and Bolton had to cut down a bunch of trees, remove the telescope’s safety bolt, and tilt the several thousand ton dish himself to catch 3C 273!

We now know that 3C 273 was one of the first quasars. Quasars are really strange objects, as Maarten Schmidt found out to his credit when he sat down to decipher the spectrum of 3C 273. He realised that many of the lines corresponded to hydrogen! But the lines were red-shifted: this meant that 3C 273 was moving away from us. It was receding away from us at 47,000 kilometres per second, which meant that it must be 3 billion light years away!

Scientists now know that quasars are actually supermassive black holes at the center of galaxies, eating the material around them at a furious pace. Gravity is so strong close to the black hole that electrons are ripped apart from the atoms in the gas, forming a plasma. The plasma now starts to accelerate as it approaches the black hole further, until it is moving at speeds close to the speed of light! Whenever anything charged moves at those speeds, it starts to radiate; and since quasars are eating so much of plasma so quickly, they radiate a lot of energy (enough to outshine their host galaxy!). They are some of the brightest and oldest objects in the Universe.

Staring into the barrel of a gun…

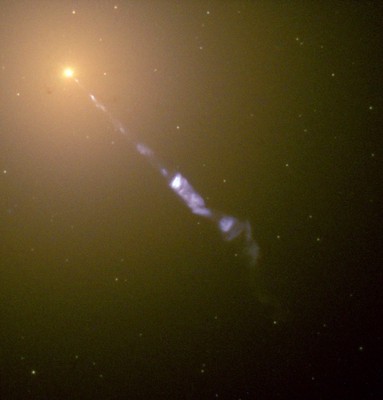

But quasars don’t just eat things: sometimes, they eject material out, in the form of jets. These jets of plasma are speeding away at close to the speed of light too! Quasars like this are called active galactic nuclei, or AGNs. These jets emit everything, from radio waves to $\gamma$-rays. They can stretch across several light years (for example, look at this one, seen by the Hubble while observing the AGN M 87; the jet is at least 5,000 light years across!).

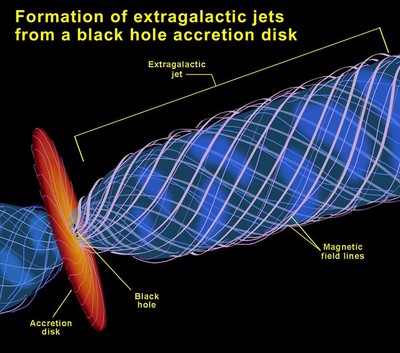

But wait up: if nothing, not even light, can escape from a black hole, how are they emitting jets in the first place? They use some nifty tricks! A lot of black holes rotate (that is, spin on their own axis). As they do, they curve space into swirls, like that foam on the top of your cappacino. But the black holes that power AGNs don’t just end up swirling space: they swirl up the magnetic fields too! These magnetic fields came from that spinning disk of plasma around them. The field lines get all twisted until they form a long helix. This can take particles from that same disk and spit them out in the form of a jet1 (see the figure below).

Sometimes these jets are pointed almost at us, like the barrel of a gun! When this happens, we call it a blazar! Blazars are basically quasars, just viewed from a different point of view. When these objects were first discovered, scientists thought they were all different from one another, which is why they all have their own names. It is only in the past few decades that we have begun to understand how supermassive black holes emit these jets, which has led to a unified theory of these objects.

Who says we haven’t got a unified theory?

Gazing into our astrochemical past.

So when astronomers pointed their radio telescopes at blazar PKS 1830-11, they thought they knew what to expect. But, as is usual in this thing we call science, they were wrong. Where they expected to see a star-like object, they instead saw a distorted image (see below). There was a faint ring, bound by two diagonally opposite blobs of light. They weren’t expecting it, but they knew what this was: a gravitational lens! Since gravity can distort space, it can also bend light, sort of like the lens in someone’s spectacles. This bending makes objects, especially massive ones, like galaxies and star clusters, as lenses. They bend the light behind them into arcs segments and rings. So when we got the first images of PKS 1830-11, we knew what we were looking at: there was something in the way! By calculating the amount of distortion, we could even estimate how massive the object blocking our line of sight was. Turns out, a galaxy was blocking and bending all the light from our blazar. This galaxy is so far away that it is like looking almost 7 billion years into our Universe’s past!

(**e** for **enhanced**) array.](/post/blazar_chem/PKS_1830_211_MERLIN_5_GHz_huba26ac9515961d08fad26bfe554ee64d_106992_0643c22ef68afb972d177f79a8fb2ebc.gif)

But scientists didn’t know the jackpot they had got on their hands yet. You see, the galaxy wasn’t just in the way: it was almost head-on. This meant that the light from the blazar, which was being bent by our galaxy, was passing through that galaxy’s disk of gas and dust, before reaching our telescopes. So when scientists decided to survey PKS 1830-11 for the first time, they ended up being surprised again: they found 34 different species of molecules there! How did that happen? When we throw light waves on to molecules, they end up absorbing the light. But they do this in a weird way: they only absorb certain wavelengths of light. So when the light from the blobs passed through the galaxy’s disk, molecules that were present in the gas absorbed some of that light. Depending on which wavelengths got absorbed, we could tell which molecules were present in that galaxy!

That means that only we detected molecules in a galaxy far, far away, but we discovered molecules that were formed more than 7 billion years ago! This helps us study a lot of things. We can study how the Universe was enriched in all the chemical elements we know through the explosion of stars, by looking at the ratios of isotopes in our molecules. We just didn’t detect $\ce{SiO}$, we also got $\ce{^{29}SiO}$ and $\ce{^{30}SiO}$. So we can now find out how much was $\ce{^{28}Si}$ there, compared to $\ce{^{29}Si}$ or $\ce{^{30}Si}$. As it turns out, the ratios then and now are quite different. This means that there wasn’t a lot of material being contributed from the explosions of low mass stars; most of it was coming from the discharges and explosions of massive stars!

We can even probe if there were any variations in the fundamental constants of physics on cosmological time scales. Because whatever your textbooks may tell you, physicists do not take it for granted that the fundamental constants, like the electron mass, say, were always “constant”. It could be that they had very different values in the past, and they evolved to have the values they do now. To test that, scientists often look at objects, like PKS 1830-11, that are very far away. In our case, since astronomers found a lot of molecules, they could just see if their calculations of where the absorbed wavelengths should be agreed with where they were. Since they had to use many of the fundamental constants we have now to do that, if their answers came out way off the actual values, we could say that constants have changed! But don’t fret, the constants are safe: if they have changed, the change is too small.

PKS 1830-211 is now known to have at least 42 different species of molecules2 : it is, in fact, the extragalactic object with the largest number of space molecules detected yet. Some of those species are (from2):

| Number of atoms | Molecules discovered |

|---|---|

| 1 atom | $\ce{H}$, $\ce{C}$ |

| 2 atoms | $\ce{CH}$, $\ce{OH}$, $\ce{CO}$, $\ce{^{13}CO}$, $\ce{CS}$, $\ce{C^{34}S}$, $\ce{SiO}$, $\ce{^{29}SiO}$, $\ce{^{30}SiO}$, $\ce{NS}$, $\ce{SO}$, $\ce{SO^{+}}$ |

| 3 atoms | $\ce{NH_{2}}$, $\ce{H_{2}O}$, $\ce{H_{2}^{17}O}$, $\ce{C_{2}H}$, $\ce{HCN}$, $\ce{H^{13}CN}$, $\ce{HC^{15}N}$, $\ce{HNC}$, $\ce{HN^{13}C}$, $\ce{H^{15}NC}$, $\ce{N_{2}H^{+}}$, $\ce{HCO^{+}}$, $\ce{H^{13}CO^{+}}$, $\ce{HC^{18}O^{+}}$, $\ce{HC^{17}O^{+}}$, $\ce{HOC}$, $\ce{HOC^{+}}$, $\ce{H_{2}S}$, $\ce{H_{2}^{34}S}$, $\ce{H_{2}Cl^{+}}$, $\ce{H_{2}^{37}Cl^{+}}$, $\ce{HCS^{+}}$, $\ce{C_{2}S}$ |

| 4 atoms | $\ce{NH_{3}}$, $\ce{H_{2}CO}$, $\ce{l-C_{3}H}$, $\ce{HNCO}$, $\ce{HOCO^{+}}$, $\ce{H_{2}CS}$ |

| 5 atoms | $\ce{CH_{2}NH}$, $\ce{c-C_{3}H_{2}}$, $\ce{l-C_{3}H_{2}}$, $\ce{H_{2}CCN}$, $\ce{H_{2}CCO}$, $\ce{C_{4}H}$, $\ce{HC_{3}N}$ |

| 6 atoms | $\ce{CH_{3}OH}$, $\ce{CH_{3}CN}$, $\ce{NH_{2}CHO}$ |

| 7 atoms | $\ce{CH_{3}NH_{2}}$, $\ce{CH_{3}C_{2}H}$, $\ce{CH_{3}CHO}$ |

References and Further Reading:

Electromagnetic extraction of energy from Kerr black holes, Blandford, R. D. and Znajek, R. L., Mon. Not. R. astr. Soc. (1977) 179, 433-456: In this germinal paper, the authors proposed, for the first time, a mechanism that could extract energy from the rotation of black holes, and explain the mysterious mechanism behind the emission of jets by active galactic nuclei. ↩︎

An ALMA Early Science survey of molecular absorption lines toward PKS 1830 − 211, Muller, S., et al., A&A 566, A112 (2014): This was the second (and latest) survey for molecules towards PKS 1830-211, using the Atacama Large Millimetre Array (ALMA). The count of extragalactic detections was raised to 42, from a previous record of 34 detections. This made PKS 1830-211 the extragalactic source with the largest number of detected molecules. ↩︎